You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Why Europe Keeps Failing........ merged with "EU Seizes Cypriot Bank Accounts"

- Thread starter Kirkhill

- Start date

- Reaction score

- 33

- Points

- 560

Greek voters are trying to suck and blow at the same time: "We want debt relief, but we don't want to take any of the steps needed to rebuild the economy or get out of the debt crisis!"

The NO vote was a tantrum of two year olds who were told there is no more ice cream and cake.

Looking at who they elected and the sorry lot of Greek politicians in general, there is no one available who could actually roll up their sleeves and do the hard work needed to fix things (and if there was, no voter would ever mark the ballot for them). The arrival of "The Man on the White Horse" is looking more and more plausible every day for the Greeks, and who knows how appealing that might look for some of the other members of the PIIGS nations if the debt crisis puts their economies under pressure?

The NO vote was a tantrum of two year olds who were told there is no more ice cream and cake.

Looking at who they elected and the sorry lot of Greek politicians in general, there is no one available who could actually roll up their sleeves and do the hard work needed to fix things (and if there was, no voter would ever mark the ballot for them). The arrival of "The Man on the White Horse" is looking more and more plausible every day for the Greeks, and who knows how appealing that might look for some of the other members of the PIIGS nations if the debt crisis puts their economies under pressure?

daftandbarmy

Army.ca Dinosaur

- Reaction score

- 26,744

- Points

- 1,160

Greece!

A... bout...... (wait for it) TURN!

A... bout...... (wait for it) TURN!

- Reaction score

- 0

- Points

- 210

From the Telegraph: Greece news live: Germany readies five-year temporary Grexit plan after finance ministers fail to reach agreement

24 hours to save the euro

Here's our wrap of events from another incredible night which has pushed Greece ever closer to a eurozone exit.

The German government has begun preparations for Greece to be ejected from the eurozone, as the European Union faces 24 hours to rescue the single currency project from the brink of collapse.

Nine hours of acrimonious talks on Saturday night, saw finance ministers fail reach an agreement with Greece over a new bail-out package, accusing Athens of destroying their trust. It leaves the future of the eurozone in tatters only 15 years after its inception.

In a weekend billed as Europe’s last chance to save the monetary union, finance ministers will now reconvene on Saturday morning ahead of an EU leaders' summit later in the evening, to thrash out an agreement or decide to eject Greece from the eurozone.

Should no deal be forthcoming, the German government has made preparations to negotiate a temporary five-year euro exit, providing Greece with humanitarian aid and assistance while it makes the transition.

A plan drafted by Berlin's finance ministry, with the backing of Angela Merkel, laid out two stark options for Greece: either the government submits to drastic measures such as placing €50bn of its assets in a trust fund to pay off its debts, and have Brussels take over its public administration, or agree to a "time-out" solution where it would leave the eurozone.

- Reaction score

- 4,341

- Points

- 1,160

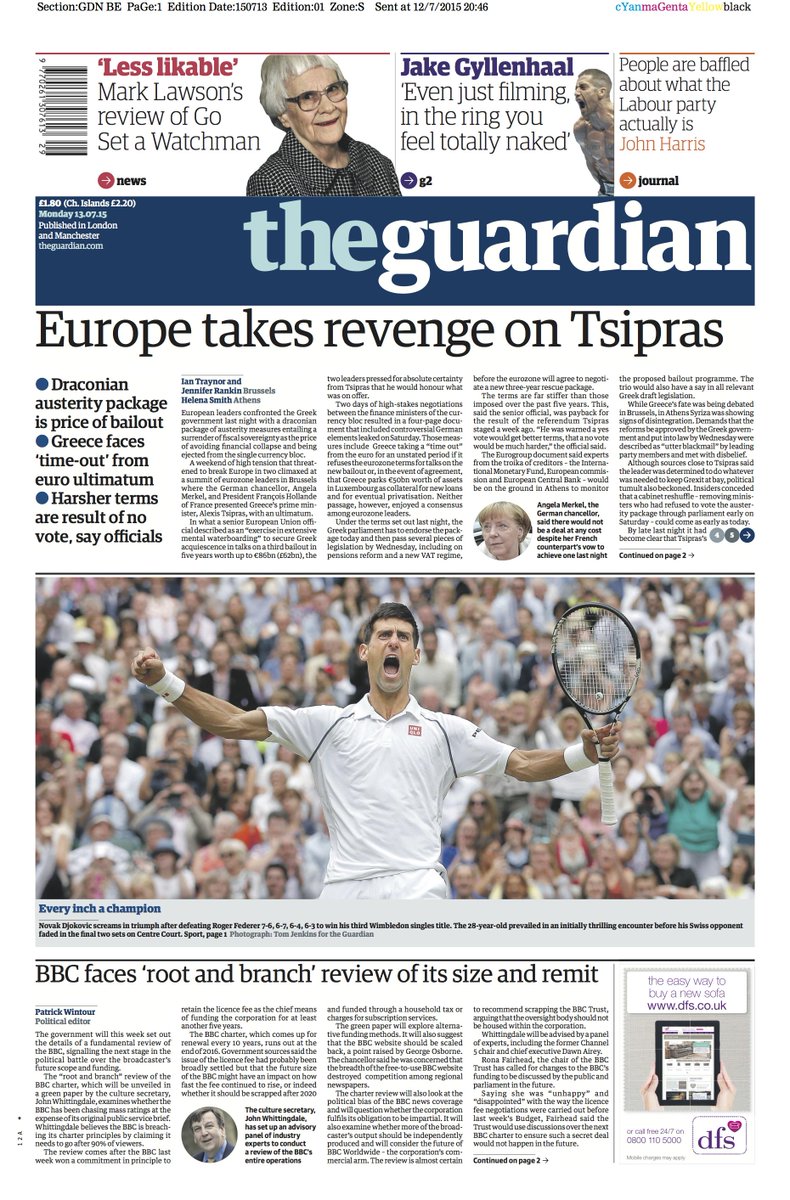

I'm no great fan of The Guardian, but there is more than just a sliver of truth in this ...

On a more serious not, in this article, which is reproduced under the Fair Dealing provisions of the Copyright Act from Foreign Affairs, Prof Jan-Werner Müller explains the dilemma that faces Bundeskanzlerin Merkel as she tries to save the Euro and her political career:

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/greece/2015-07-10/merkel-method

I think Prof Müller hits a key point about midway through: if Europe fails it will be because France has screwed the pooch, again. Wolfgang Schäuble's fond memories of the halcyon days of Franco-German cooperation, in the 1980s, are wrong: the French were duplicitous then and they are now. They lie, consistently, to their partners, and their partners, the Dutch, the Finns and the Germans all know it, but they choose to live in a cloud cuckoo land because the original "master plan" (written by Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman and Paul Henri Charles Spaak) insisted that France must be at the centre (and that Germany must be brought to heel). It was a political necessity circa 1960, a political advantage in 1970, but always, even in 1980, was and is, in 2015, a fiction.

Edited to add:

Banx may well have it just about right:

http://banxcartoons.co.uk/

On a more serious not, in this article, which is reproduced under the Fair Dealing provisions of the Copyright Act from Foreign Affairs, Prof Jan-Werner Müller explains the dilemma that faces Bundeskanzlerin Merkel as she tries to save the Euro and her political career:

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/greece/2015-07-10/merkel-method

The Merkel Method

Germany and the Greek Crisis

By Jan-Werner Müller

July 10, 2015

"If the euro fails, Europe fails.” This dictum must be the most often-quoted sentence from Europe’s most powerful politician, a figure otherwise hardly known for making straightforward statements or clear commitments. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s success over the past ten years (she is already the longest-serving German chancellor after Konrad Adenauer and Helmut Kohl) is often attributed to her uncanny ability to let political developments and debates take their course—and only to stake out a position when she can be sure that her position will be on the winning side. However, in the eyes of her German critics, her apparent commitment to saving the euro no matter what has made her vulnerable to blackmail. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras in particular has been betting that, for all German elites’ moralizing, the country will not, in the end, want a Grexit. And so, as is so frequent in the EU, a great policy fudge will be found that will allow all concerned to somehow save face. But Tsipras should not be so sure. A number of developments—not least profound transformations within German political culture that Germany’s partners have barely begun to understand—make it risky to bank on Germany keeping Greece.

As with all EU leaders, Merkel’s primary concern is her domestic electorate—and, ultimately, her own party. The Christian Democrats were once the main force for European economic and political integration; Kohl risked his political life for it. But today, there is little idealism left; the only major figure who still openly advocates for a “United States of Europe” (without ever spelling out what that would mean in practice) is Germany’s defense minister, Ursula von der Leyen. And arguably, she is doing so mainly to sharpen her profile as a major rival to Merkel, who has remained conspicuously silent on Europe’s final shape.

Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany’s finance minister and a kind of political son of Kohl, remains a European by conviction, but even he has been lobbying for Grexit inside the government. Like a number of other CDU politicians and intellectuals, he no longer accepts the notion that integration is a one-way path. Long taboo, the “reversibility” of eurozone membership (or even EU membership) is now less controversial. Some point to the lack of state capacity in Greece; others mention that Hungary, where the government seems bent on creating an illiberal state, no longer subscribes to the fundamental EU values codified in the European treaties. An increasing number of voices advocate a return to a position that Schäuble himself held in the early 1990s. They argue that there needs to be a “core Europe,” what Germans call Kerneuropa, and, by definition, a peripheral Europe—states that are only partially integrated into the EU. In core Europe, there would be monetary, fiscal, and political union (with the last hardly ever clearly defined). Peripheral Europe would be made up of states that, so the unspoken assumption goes, are sometimes genuinely unwilling and sometimes simply unable to follow certain common rules. In other words, for dysfunctional states like Greece, there is no place in Kerneuropa.

Germans are mistaken, though, if they believe that such a core Europe, which appears to come down to Northern Europe plus France, could exist. They don’t seem to understand that France is far from rushing to share sovereignty in general or enter a fiscal union with other countries in particular. German politicians and intellectuals treat the current French government with more or less open contempt; likewise, they (and much of the rest of Europe) do not take particularly seriously ongoing French efforts to mediate between Europe's north and south with a view toward keeping Greece in the euro. They can argue, of course, that an overwhelming number of French citizens themselves, or so polls suggest, trust Merkel more than French President François Hollande to solve the crisis. And it is true that France would not really be a constraint if Germany wanted to push hard for Grexit. But that doesn’t mean that France would willingly be part of core Europe, especially, as only Schäuble (with his memory of what Franco-German friendship felt like in the 1980s) seems to intuit, it doesn’t feel like an equal partner.

Something similar is true of potential German domestic opposition to Grexit. Merkel’s junior partners in government, the Social Democrats, have used all their negotiating power to get a better deal for workers at home; they have effectively abandoned Europe and trans-continental solidarity. There is no more talk of “eurobonds” or other means to help economically and socially weaker countries. Instead, Sigmar Gabriel, the chairman of the Social Democrats, has tried to be more Merkelian than Merkel. After the recent Greek referendum, he attacked Tsipras personally in a way that the chancellor did not. He is clearly worried that letting Merkel manage the eurocrisis unchallenged will cost him votes in the next federal election in 2017. And he is responding to public opinion (or at least published opinion) according to which the government needs to be tough (and Merkel an “Iron Chancellor”—Bild, the country’s largest tabloid, depicted her with a helmet à la Bismarck this past Tuesday).

There is yet another factor that makes Grexit more plausible than ever from Merkel’s point of view: the anti-euro party “Alternative for Germany” (AfD)—which narrowly failed to enter the parliament in the last federal elections in 2013 but is a strong presence in a number of state assemblies—has been consumed with infighting. The AfD has also drifted to the right. Its leaders are seemingly more concerned about asylum seekers and refugees than economic policy. Previously, Grexit would have played into the hands of this party, which used to be run by professors and industrialists who sought to offer a conservative alternative to Merkel's and the CDU’s drift toward a more mushy middle. Now, the professors are leaving the AfD in droves, and a drastic decision on Greece would not necessarily benefit the party, which, like many previous right-wing populist parties in Germany, could end up completely marginalized.

None of this is to say that the German chancellor’s horizon is fully obscured by petty domestic party politics. It is likely that she has started thinking about what the history books will say and that her primary ambition for this term in office, and potentially one more, will be to leave behind a stable and prosperous EU. So far, she has pursued the goal of a highly competitive continent (her vision never seems to go much beyond economics) by making common rules tighter and effectively tasking courts with enforcing limits on debts. However, as the political scientist R. Daniel Kelemen has pointed out, in comparison with nineteenth-century United States, there is little reason to think that a German legalistic approach will succeed in constraining governments in a quasi-federation like the EU. Only by letting some states go bankrupt can the eurozone eventually ensure discipline in a way that constitutional structures, no matter how well-crafted in Berlin, might not. Letting Greece go, in other words, might be the best way for Merkel to get what she wants.

I think Prof Müller hits a key point about midway through: if Europe fails it will be because France has screwed the pooch, again. Wolfgang Schäuble's fond memories of the halcyon days of Franco-German cooperation, in the 1980s, are wrong: the French were duplicitous then and they are now. They lie, consistently, to their partners, and their partners, the Dutch, the Finns and the Germans all know it, but they choose to live in a cloud cuckoo land because the original "master plan" (written by Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman and Paul Henri Charles Spaak) insisted that France must be at the centre (and that Germany must be brought to heel). It was a political necessity circa 1960, a political advantage in 1970, but always, even in 1980, was and is, in 2015, a fiction.

Edited to add:

Banx may well have it just about right:

http://banxcartoons.co.uk/

- Reaction score

- 4,341

- Points

- 1,160

Not at all surprisingly, Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman is outraged at the demands being made of Greece and he expresses that in this article which is reproduced, without further comment from me, under the Fair Dealing provisions of the Copyright Act from the New York Times:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/?8dpc&_r=1

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/?8dpc&_r=1

Killing the European Project

Paul Krugman

JULY 12, 2015

Suppose you consider Tsipras an incompetent twerp. Suppose you dearly want to see Syriza out of power. Suppose, even, that you welcome the prospect of pushing those annoying Greeks out of the euro.

Even if all of that is true, this Eurogroup list of demands is madness. The trending hashtag ThisIsACoup is exactly right. This goes beyond harsh into pure vindictiveness, complete destruction of national sovereignty, and no hope of relief. It is, presumably, meant to be an offer Greece can’t accept; but even so, it’s a grotesque betrayal of everything the European project was supposed to stand for.

Can anything pull Europe back from the brink? Word is that Mario Draghi is trying to reintroduce some sanity, that Hollande is finally showing a bit of the pushback against German morality-play economics that he so signally failed to supply in the past. But much of the damage has already been done. Who will ever trust Germany’s good intentions after this?

In a way, the economics have almost become secondary. But still, let’s be clear: what we’ve learned these past couple of weeks is that being a member of the eurozone means that the creditors can destroy your economy if you step out of line. This has no bearing at all on the underlying economics of austerity. It’s as true as ever that imposing harsh austerity without debt relief is a doomed policy no matter how willing the country is to accept suffering. And this in turn means that even a complete Greek capitulation would be a dead end.

Can Greece pull off a successful exit? Will Germany try to block a recovery? (Sorry, but that’s the kind of thing we must now ask.)

The European project — a project I have always praised and supported — has just been dealt a terrible, perhaps fatal blow. And whatever you think of Syriza, or Greece, it wasn’t the Greeks who did it.

- Reaction score

- 33

- Points

- 560

Reality is seeping into Greece, and they are not liking it at all....

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/11/greeks-future-europe-austerity-eurozone

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/11/greeks-future-europe-austerity-eurozone

Greeks resigned to a hard, bitter future whatever deal is reached with Europe

Greece has become so gloomy that even escapism no longer sells, the editor of the celebrity magazine OK! admits. “All celebrity magazines have to pretend everything is great, everyone is happy and relaxed, on holiday. But it is not,” says Nikos Georgiadis.

Advertising has collapsed by three-quarters, the rich and famous are in hiding because no one wants to be snapped enjoying themselves – and even if OK! did have stories, a ban on spending money abroad means it is running out of the glossy Italian paper that the magazine is printed on.

“We have celebrities calling and asking us not to feature them because they are afraid people will say ‘we are suffering and, look, you are having fun on the beach’,” Georgiadis says. “One did a photoshoot but then refused to do the interview. They don’t want to be in a lifestyle magazine.”

Live Greece debt crisis: Athens fights against temporary Grexit plan - live

Greece is resisting its creditors’ demands for even more austerity measures and reforms in Brussels tonight, as bailout talks go to the wire

It might be easy to mock the panic of Greece’s gilded classes, if the only thing affected was the peddling of aspiration and envy. But the magazine provides jobs to many people whose lives are a world away from the ones they chronicle, and like thousands of others across Greece they are on the line as the government makes a last-ditch attempt to keep the country in the euro.

“If we go back to the drachma, they told us the magazine will close. It’s possible we won’t have jobs to go to on Monday,” Georgiadis says bluntly, as negotiations with Greece’s European creditors headed towards the endgame.

Prime minister Alexis Tsipras pushed a €13bn austerity package through parliament early on Saturday, overcoming a rebellion by his own MPs and sealing a dramatic and unexpected transformation from charismatic opponent of cuts to their most dogged defender.

It seemed like nothing so much as a betrayal of those he had called out in their millions less than a week earlier to reject an almost identical package of painful reforms. Greece’s creditors had soon made clear though that they were not ready to improve bailout terms, even to keep the country in the euro.

And so after painful days of cash shortages, closed banks, dwindling supplies of anything imported, from medicine to cigarettes, and mounting fear, the extraordinary U-turn was met with more resignation than anger.

“It’s very hard but in this time we don’t have any other solution,” says Poppi Papadopolou in the nearly deserted cafe that she has run for three decades, less than a week after she had cast her own vote with Tsipras and against more austerity. “We must be flexible.”

The last five years have been a time of retrenchment, and the last two weeks ones of bare survival. The lights and air conditioning are off, and the trays of cutlet, sausage, bacon, Greek salads and other sandwich fillers that were once kept brimful boast only enough for a single lunch.

“Until things go back to normal, we have costs but no income,” she says, as her sole customer slowly sips a coffee in the dim interior. She had learned to be happy when she could break even; now she is raiding savings that are all but gone, and reckons the drachma would finish them off.

That is a possibility which the new austerity plan has not yet entirely banished. The proposals have been welcomed by many but not all of Greece’s European partners; German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble “believes Athens’s plans are insufficient and is against further talks”, the newspaper Bild reports.

Marianthi Velentza, a stationery shop owner who says she had to let her staff go and now works twice as hard in her 40s as she did 20 years ago, says she never expected the referendum would stave off more austerity.

Stationery shop owner Marianthi Valentza Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Stationery shop owner Marianthi Valentza says she thought the referendum was ‘more or less a game, to get the bailout deal without public disappointment’. Photograph: Panagiotis Moschandreou/Panagiotis Moschandreou

“People are a bit romantic, and thought that it would be a strong argument for a different arrangement with Europe,” she says. “I thought it was more or less a game, to get the bailout deal without public disappointment.”

She has become used to fielding her daughter’s questions about why they don’t have holidays or so many new clothes now, even if she finds it painful, but fears that crashing out of the European Union would cast a longer shadow over her child’s future.

“It would affect the business: but it’s not only about me, it’s also about my kid. I don’t want her to have problems going abroad to work or study, getting visas like we used to.”

One of the big concerns of the creditors scrutinising the deal is whether Greek authorities will follow through on what they have promised. It is a concern echoed by many businesspeople at home, turned cynical by years of unmet promises to cut corruption, tax fraud and red tape. “The problem is, will they actually fulfil it?” asks Ramesh Basra, owner of travel agency GR Bollywood, a 22-year-old business that has slowly unravelled in the crisis.

He laid off all seven employees in January and runs what’s left of the company alone, frustrated by the inability of his adopted homeland to cash in on its assets, but convinced the industry will eventually recover. “It is the best destination in the world: the beaches, the climate,” he says. “I like Greece even with all these problems. I will stay until the last battle.”

Basra even hopes that his business might eventually benefit a little from the package if promises to cut red tape and tax avoidance are made good. Cheating is so rampant at the moment that it effectively penalises honest firms, other entrepreneurs say as well.

“I would prefer a stricter system, because it is for the good of our country. Greeks are specialists in avoiding taxes,” says Thanasis Pouros, who owns an upmarket gym in a smart part of the city, where he says the economic crisis has been the only topic of conversation for weeks, and where now several clients have stopped coming to class. “We were all expecting that the time would come when the country would have to give answers for the wealth that some people created too easily.”

Among many Greeks there is a sense of frustration that their lives are being curtailed to repay loans that they feel bought little for ordinary citizens. Much of the cash was siphoned off by corrupt officials, and the last few years of cuts have served only to pay interest to creditors, they say.

“The government failed the country, they made money from the country,” says florist Vygontzas Giorgos. “Now we should be asking: who did you give money to, who is responsible for the stolen money? It’s not that we don’t want to pay: it’s that we don’t have the money.”

- Reaction score

- 7,388

- Points

- 1,160

tomahawk6 said:Can France be far behind ?

This Frenchman doesn't think so.

France is the sick man of Europe, says former French prime minister François Fillon

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/11734627/France-is-the-sick-man-of-Europe-says-former-French-prime-minister-Francois-Fillon.html

That might also explain this:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11734681/The-countries-happy-to-see-Greece-leave-the-eurozone.html

You are known by the company you keep.

- Reaction score

- 4,341

- Points

- 1,160

So, correct me if I'm wrong, please, but it seems to me that Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras spent a few weeks (and a shit load of political capital) blustering and bullying his way into a deal that is markedly worse than what was, originally, on offer ...

- Reaction score

- 0

- Points

- 210

Sure seems to be the case.

From the Economist: Greece signs up to a painful, humiliating agreement with Europe

From the Economist: Greece signs up to a painful, humiliating agreement with Europe

AT ONE point during marathon euro-zone talks in Brussels on the evening of July 12th, Alexis Tsipras was a few minutes late returning from a break. A rumour took flight: the Greek prime minister, facing brutal demands from his 18 fellow euro-zone leaders in exchange for an agreement to begin talks on a new bail-out, had fled the building. It turned out that he was in the bathroom.

That it seemed plausible for Mr Tsipras to have pulled a personal Grexit sheds light on the extraordinary pressure the prime minister faced during the all-night talks. At 6am, locked in discussions over a controversial privatisation fund with Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, and François Hollande, the French president, Mr Tsipras did indeed come close to walking out. But spurred by pressure from Donald Tusk, the chair of the summit, the three eventually managed to forge a deal that could form the basis of a multi-billion-euro bail-out, Greece’s third in five years.

In exchange for the package, which could amount to as much as €86 billion ($95 billion) over three years, Mr Tsipras has had to sign up to precisely the sort of demands his Syriza party railed against during its successful election campaign in January. The proposals in a compromise deal offered by Mr Tsipras the previous week, most of which were overwhelmingly rejected by Greek voters in a referendum a few days earlier, mark just the beginning of the new deal. Those pledges, on matters like VAT and pension reform, must be legislated by the Greek parliament no later than July 15th. A week later further legislation must follow, including a total overhaul of Greece’s judicial system.

But that is just the start, as Mrs Merkel had warned it would be at a previous summit last week. Greece must also enact further pension reforms, open up professions, loosen trading rules, privatise its electricity network, reform its labour market and strengthen its banks. Once that is out of the way, Mr Tsipras’s government, if it is still standing, will have to produce plans for “de-politicising” the Greek administration, a task that has eluded every government since Greece obtained its independence from the Ottomans in 1832. It must accept complete oversight from the hated “institutions” (once known as the troika) who will return to Athens to oversee the work of Greek officials. At the insistence of the Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, it will have to roll back any legislation it has passed since taking office that violates previous bail-out agreements (or compensate for their consequences by passing new laws). Most painful of all, it will have to deposit what the seven-page summit statement calls “valuable Greek assets” into an independent privatisation fund with the aim of raising €50 billion over the course of the bail-out.

These commitments, the statement notes dryly, “are minimum requirements to start the negotiations with the Greek authorities”. Talks over the details of the bail-out, including the fiscal path the battered Greek economy will have to tread, will follow, and they will hurt. Meanwhile, Mr Tsipras must hope that the other euro-zone parliaments that need to approve a bail-out (at current count, six: Germany, the Netherlands, Estonia, Finland, Slovakia and Austria) will find a way to overcome the utter vaporisation of trust between Greece and its creditors that last night’s talks laid bare. He must also hope that euro-zone finance ministers, meeting today in Brussels for the latest in an apparent never-ending carousel of summits, will strike agreement on the €12 billion in short-term financing Greece needs to meet its immediate obligations (ie, before the bail-out is agreed), including a €4.2 billion bill to the European Central Bank on July 20th. Ideas for how to manage that are thin on the ground. And Mr Tsipras must finally hope that Greece’s gasping banks can stay afloat for the next few days until the ECB feels minded to increase its liquidity support; today it maintained its current level of €89 billion.

As the details of the agreement emerged last night angry Greeks and their comrades spawned a social-media hashtag: #ThisIsACoup. Even if that is a stretch, it is worth asking what Mr Tsipras has to show for all this misery. He can point to four wins, most of them minor. First, Greece’s departure from the euro is no longer an immediate prospect. A plan for a temporary Grexit, pushed by Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany’s finance minister, was instantly scrubbed by the leaders last night. Second, Mr Tsipras won a concession on the proceeds of the €50 billion privatisation fund: half of it will be used to recapitalise Greece’s threadbare banks and one-quarter for unspecified “investments”, something Mr Tsipras will no doubt trumpet loudly in the difficult parliamentary debates to come in Athens. (Mrs Merkel had wanted to devote all the money to paying down debt.) Third, the deal could unlock up to €35 billion in investment from the European Commission, although the details remain vague. And finally, the statement contains a pledge to consider, “if necessary”, measures designed to loosen Greece’s debt load, such as an extension of maturities. Although Greece’s debt profile means the immediate impact of any such restructuring would be next to zero, it is nonetheless a meaningful achievement for a government that has ceaselessly urged a relaxation of its financial obligations.

As for the rest of the euro zone, there will no doubt be relief that the latest chapter of the Greek crisis has been closed, even if many more are to come. But when they emerge from their post-summit slumbers they will face two awkward questions. First, how can they expect a government whose identity was forged in opposition to austerity and foreign tutelage to implement reforms that stymied its far more pliant predecessors? And second, how can a euro zone that was created to drive integration and foster trust between its members thrive when it appears to have had precisely the opposite effect?

E.R. Campbell said:So, correct me if I'm wrong, please, but it seems to me that Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras spent a few weeks (and a crap load of political capital) blustering and bullying his way into a deal that is markedly worse than what was, originally, on offer ...

He played a a game of chicken with Germany and lost. Badly. You don't play chicken with a Panzer, when you are driving a Namco Pony...

- Reaction score

- 33

- Points

- 560

The Greek financial crisis explained as a morality play:

http://pjmedia.com/blog/in-the-end-greeces-war-on-debt-is-a-morality-problem/?singlepage=true

http://pjmedia.com/blog/in-the-end-greeces-war-on-debt-is-a-morality-problem/?singlepage=true

In the End, Greece’s War on Debt Is A Morality Problem

A majority of Greeks simply do not believe debt must always be repaid.

by Tyler O'Neil

July 13, 2015 - 9:32 am

How can a country which accepted billions of dollars in loans think it’s acceptable not to pay it back? Simplistic as it sounds, the Greek conundrum stems from denying the basic principle that you can only spend what you earn.

Greece may have just reached another bailout agreement with Europe, but the defiance of last Sunday remains — 61% of Greeks voted against a plan upon which their government had already agreed. They voted against paying their debt. The agreement this week forces more government cutbacks, and will likely prolong the rage of many Greeks who oppose the necessary reforms brought on by indebtedness.

How We Got Here

Greece has struggled with high debt, high unemployment, and political turmoil since 2009. In the early years of the euro (2001-2008), Greece borrowed heavily to build up infrastructure — think the 2004 Summer Olympic Games — but its economy nearly tripled at the same time. Yet after the financial crisis of 2008-2009, the growth stopped — but the borrowing continued.

In 2010, the government realized it needed to cut back, and introduced the much-maligned austerity-cutting salaries for government workers. Later that year, the European Union (EU), European Central Bank (ECB), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed to a €110 billion bailout over three years. In 2012, a second bailout deal increased the total to €246 billion by 2016 — 135% of Greece’s 2013 gross domestic product (GDP). A third bailout is forthcoming.

After seven large government cutbacks between 2010 and 2013, Greece finally took in more money than it paid out, reaching a budget surplus of 1.5% for the 2013 financial year.

Austerity worked.

The political strain proved too much, however. Between 2014 and 2015, the far-left Syriza Party gained control in numerous elections. The sporadic revolts and violent opposition to government cutbacks had empowered a political movement which favored the same government largesse and deficits which put Greece in the hole in the first place.

The “Nazi” Angela Merkel

Greece is deeply in debt, and Germany holds the IOUs. German Prime Minister Angela Merkel has insisted that Greece pay back its creditors and keep its promise to enact further government cutbacks. Incensed Greeks responded with, well, graffiti, giving Merkel a Hitler moustache, and comparing their creditors to the Nazi occupation which starved 300,000 Greeks in World War II.

Prominent Keynesian economist Thomas Piketty gives an intellectual veneer to this anti-German backlash. He tells Merkel to remember 1953, when numerous Western powers — Greece included — restructured West Germany’s debt, cutting it by 50%. Germany is hypocritical to demand Greece’s repayment and cutbacks when Greece did not demand such terms in the 1950s, Piketty argues.

As Business Insider’s Mike Bird notes, this argument proves utterly baseless. While Germany’s situation in 1945 was comparable to Greece’s today — Germany’s debt was over 200% of its GDP then, Greece’s is 177% of its GDP now — by 1953 the situation was far different.

In 1948, Germany reformed its currency — wiping out approximately 90% of Germany’s cash holdings and deposits. This austerity makes Greece’s recent reforms look like a cakewalk, but it worked.

Unlike Greece in 2015, the German economy in 1953 was growing. More than that, the country had generated a trade surplus and a government surplus — the country exported more goods than it imported and the government brought in more taxes than it spent. Germany reliably started paying back its debt. Greece, however, needs to import more than it can export, and is struggling to balance its books.

Finally, Germany’s 1950s creditors had larger concerns than debt repayments — they were in the middle of the Cold War. It was in the interest of NATO countries to strengthen an economic power in Germany that could be a strong bulwark of Western freedoms from the encroaching Soviet bloc. Germany’s economy was central to Europe’s prosperity, and bolstering both was a crucial Cold War aim.

Corruption is a Greek Tradition

Beneath Piketty’s superficial argument looms a stronger cultural opposition to efficient government. As the Daily Beast’s Nick Romeo explains: “The Greeks ‘Ate’ Their Way to Ruin.” In short, Greeks — unlike Lannisters — do not always pay their debts.

In Greece, corruption is a national tradition. In his book “The Full Catastrophe: Travels Among the New Greek Ruins,” James Angelos interviews a Greek man who traces tax cheating back to the days of the Ottoman Empire. “The one who didn’t pay taxes to the sultan was smart,” the Greek explained.

In 2014, the European Commission discovered that Greek citizens cheated the government out of €10 billion in uncollected consumption taxes. Another study estimated that self-employed Greeks failed to report €28 billion of taxable income in 2009.

Around the time of the first Greek bailout, the government found almost 17,000 swimming pools in rich neighborhoods that were never declared on tax forms.

In addition to tax evasion, welfare fraud runs rampant in Greece. On the island of Zakynthos, nearly 500 people with perfectly good vision claimed a blindness benefit from the Greek health ministry for years. 8,500 Greeks claimed to be over 100 years old in order to collect on pensions.

Some Greeks hated the austerity reforms because they made the government more efficient, cutting fraud which allowed people to avoid due taxes and collect undue benefits.

Hating on “Austerity”

The term “austerity” has garnered a great deal of hatred recently. President Obama called on Americans to reject the “mindless austerity” of Republicans, and the Huffington Post’s Howard Fineman argued that “Greece is Just the Beginning of the Great Austerity Backlash.”

To some people, the idea of paying back debts just seems … unfair. After all, why should a poor country have to pay rich countries?

As Victor Davis Hanson writes in National Review, “The rich Northern Europeans … could write off the entire Greek debt and not really miss what they lost. In the Greek redistributionist mindset, why should one group of affluent Europeans grow even wealthier off of poorer Europeans?”

“Athens has adopted the equality-of-result mentality that believes factors other than hard work, thrift, honesty, and competency make one nation poor and another rich,” Hanson explains. “Instead, sheer luck, a stacked deck, greed, or a fickle inheritance better explain inequality.”

This ideology of fairness over economic sense emerges throughout left-wing circles. Bloomberg Businessweek’s Michael Schuman actually criticized Germany for balancing its budget. “Rather than taking advantage of German financial strength to increase spending, Merkel balanced the national budget in 2014 for the first time in 45 years,” he chided.

Apparently, Schuman cannot praise a government that only spends what it takes in.

Progressives may hate the balanced budgets and government cutbacks that austerity entails, but that does not make such trimmings harmful or unnecessary. Austerity may have gotten America out of one of its worst depressions in 1920-1921. When the economy tanked, President Warren Harding cut taxes and spending, the market self-corrected, and America entered the “Roaring Twenties.” Franklin Roosevelt’s big government policies ten years later seemed to have the opposite effect, prolonging a possibly less great depression.

As Margaret Thatcher famously said, the problem with socialism is that “you eventually run out of other people’s money.” Then arises the simple question of morality — do you pay your debts, honor your word, keep your commitments? Greece, it seems, has a tradition of doing the opposite.

A conservative fundraiser and commentator, Tyler O'Neil has written for numerous publications, including The Christian Post, National Review, The Washington Free Beacon, The Daily Signal, AEI's Values & Capitalism, and the Colson Center's Breakpoint. He enjoys Indian food, board games, and talking ceaselessly about politics, religion and culture.

Brad Sallows

Army.ca Legend

- Reaction score

- 7,024

- Points

- 1,040

To the extent that any morality is involved, I noticed some pundits (eg. Krugman) are trying to make Germany/creditors the bad guy, not Greece/the borrower.

This post cites an article which quotes one Bernard Connolly, whose name means nothing to me but this statement is interesting:

"People misapprehend the problem of the euro when they talk about government debt crises. The problem is with the relative competitiveness of each of the nations as a whole. Adjustment within the euro area requires an internal devaluation, which means deflation or depression, or a transfer union [in which the better-off states subsidise the worse off]."

I suppose Germany isn't on board with a transfer union, which leaves the alternative stated above or an adjustment of membership.

This post cites an article which quotes one Bernard Connolly, whose name means nothing to me but this statement is interesting:

"People misapprehend the problem of the euro when they talk about government debt crises. The problem is with the relative competitiveness of each of the nations as a whole. Adjustment within the euro area requires an internal devaluation, which means deflation or depression, or a transfer union [in which the better-off states subsidise the worse off]."

I suppose Germany isn't on board with a transfer union, which leaves the alternative stated above or an adjustment of membership.

- Reaction score

- 3

- Points

- 430

What it ultimately comes down to is the Greeks need to decide between two alternatives:

1) Remain in the European Union and suffer under a policy of forced austerity and the consequences that come with it.

or

2) Leave the Union, regain control of their own economy, and suffer the consequences that come with that decision.

Either way they will suffer.

1) Remain in the European Union and suffer under a policy of forced austerity and the consequences that come with it.

or

2) Leave the Union, regain control of their own economy, and suffer the consequences that come with that decision.

Either way they will suffer.

- Reaction score

- 4,341

- Points

- 1,160

cupper said:What it ultimately comes down to is the Greeks need to decide between two alternatives:

1) Remain in the European Union and suffer under a policy of forced austerity and the consequences that come with it.

or

2) Leave the Union, regain control of their own economy, and suffer the consequences that come with that decision.

Either way they will suffer.

Or, there is the "third way," outlined in the link posted, just above, by Brad Sallows: Germany (and Finland and the Netherlands and a few others) should "leave the Euro," now, thus avoiding the inevitable crash. Over three years ago Michael Sivy, writing in Time magazine repeated a key conclusion of Bernard Connolly's book "The Rotten Heart of Europe" and suggested that Germany should leave the Euro, thus: "The weaker European countries would get to keep the euro but still get the devaluation they need, which would reduce their labor costs far less painfully than through wage cuts. In addition, the value of their outstanding debt would decline along with the value of the euro, and they would be more likely to be able to make payments on that debt and avoid defaulting."

Might there be to Euros a strong one and a weak one? Maybe, but: the weak Euro is the one that should hang together, led by France and Italy, but, as Mr Sivy suggests, "the [weak] euro would be the currency that falls in value, relative to Germany’s new national currency and also to the dollar."

Similar threads

- Replies

- 16

- Views

- 7K