ILLUSIONS OF GRANDEUR

John Anari is a West Papuan independence activist. Tom Bleming is a retired American gunrunner. Together, they want to win the South Pacific's next great freedom struggle.

In the summer of 2009, John Anari, a young political activist from the Indonesian region of West Papua, created a Facebook page. He did it using an old desktop computer with a dial-up Internet connection, in a one-room apartment in Manokwari, the provincial capital situated on West Papua’s northeastern coast. The page wasn’t a personal profile. Anari, who prides himself on being tech savvy, had created one of those the year before. The page was the first of what would become several online outposts for the West Papua Liberation Organization (WPLO), a group that Anari had founded to agitate for his homeland’s independence.

“Most freedom groups in Papua cannot access the Internet or don’t know how to use it,” Anari, now 35, said recently. “I wanted to show the world Indonesia’s crimes.”

On the WPLO page, Anari posted unclassified diplomatic cables related to West Papua’s colonial past, updates from exiled independence activists, and videos of defiant rebel leaders training for armed struggle in remote highland camps. He also shared gruesome photos of West Papuans who reportedly had been beaten, shot, or tortured by the Indonesian security forces that have controlled the western half of New Guinea, the world’s largest tropical island, since 1962. Because foreign journalists and NGOs are rarely granted entry to West Papua and are closely monitored when they are, the page opened a rare, real-time window into one of the bloodiest and best-kept secrets of the South Pacific.

As social media does, this window also functioned as a global drive-thru. Anari, who had never traveled outside Indonesia, began cultivating friendships with a motley mix of international sympathizers. To educate them about West Papua, he posted comments about international treaties and resolutions that he described as evidence of the region’s right to independence. Most people who reached out to him pledged moral support or promised to write letters to world leaders on West Papua’s behalf. But a minority of Anari’s new contacts—quixotic adventure seekers, soldiers of fortune, and crackpots claiming to represent foreign armies and intelligence agencies—volunteered a deeper commitment to the WPLO’s mission. To them, Anari emphasized his ambition to build an army from West Papua’s fractious rebel cells. Although he had no formal military training (by day he worked as an IT contractor), Anari presented himself as a man capable of leading a full-blown insurrection.

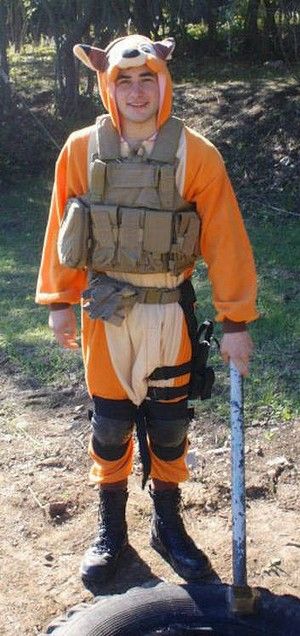

One of Anari’s first online friends credulous of his revolutionary potential was Tom Bleming, a longtime mercenary living in Wyoming. Unlike Anari, Bleming had been everywhere: After serving in Vietnam, the American became a free agent, aiding independence movements and coup plots around the globe. In 1979, he landed in a Panamanian military jail for attempting to blow up Manuel Noriega’s entourage with dynamite and diesel. When Anari contacted him for the first time, via a Facebook message in 2009, Bleming had just returned from a pro bono stint advising and supplying nonmilitary aid to the Karen National Liberation Army, a rebel group in eastern Myanmar. Then 63 and living on veteran disability payments, Bleming was considering retiring. But the West Papuan cause fired the boiler of his moral and military imagination; he later described it to me as his “last hurrah.” Over several years’ worth of messages and phone calls, Bleming offered to help Anari however he could, from making introductions to arms dealers to providing room and board in the United States.

AS SOCIAL MEDIA DOES, THIS WINDOW ALSO FUNCTIONED AS A GLOBAL DRIVE-THRU. ANARI, WHO HAD NEVER TRAVELED OUTSIDE INDONESIA, BEGAN CULTIVATING FRIENDSHIPS WITH A MOTLEY MIX OF INTERNATIONAL SYMPATHIZERS.

By 2014, a room was exactly what Anari needed: He was planning a trip to New York to meet with contacts at the United Nations and with NGOs lobbying the international body. He wanted a base of operations anywhere in the United States, and Bleming offered one with benefits. “The rebel groups in West Papua do not understand modern unconventional warfare,” Anari later told me. “Tom and his friends offered to educate me.”

Thanks to Bleming’s financial help, Anari landed in Casper, Wyoming, on an unseasonably warm afternoon in October 2014. Bleming was waiting near the airport, leaning against his beater Oldsmobile that’s plastered with bumper stickers; one bears the silhouette of an AK-47, while another sports Che Guevara’s face. He greeted his guest with military formality: “General Anari, welcome.”

Bleming lives in Lusk, an old ranching town about 100 miles southeast of Casper, best known these days for its stagecoach museum, a women’s prison, and an annual pioneer-days re-enactment called the “Legend of Rawhide.” On the drive to Bleming’s house, the pair stopped for lunch at the Ghost Town Fuel Stop & Restaurant. Over bowls of chili, they agreed that the old mercenary would serve as Anari’s unofficial military advisor, as well as his “chief protocol officer,” handling the West Papuan’s security, travel, and scheduling. Bleming invited Anari to stay in Lusk as long as he liked.

When I visited Wyoming this January, Anari was in the middle of what became a four-month stay. Our first meeting took place around a flaming oil drum on the rolling prairie; every Sunday, on 80 acres that the former gunrunner owns just beyond Lusk’s town limits, Anari and Bleming burned the trash they’d generated the previous week. Wearing his leather jacket, sunglasses, and military beret, Anari, who also carried a compact pistol, evoked a paunchy Black Panther leader circa 1965, mysteriously transported to the emptiest county in America’s emptiest state. Only the shiny emblem on his beret betrayed his even more unlikely origin. It featured the mascot of the West Papuan rebels, the cassowary: a flightless bird that can grow to 6 feet tall and that has been known to fatally attack humans with its knife-like middle claw.

The men’s fireside talk of war and independence was by then familiar to many of Lusk’s townsfolk. Since Anari’s arrival, the pair had discussed martial and diplomatic strategy in the town’s bars, in meet-and-greets with Bleming’s friends—mostly fellow ex-military and mercenary types—and with local journalists. “We’re lining up people to handle everything from refineries to civil aviation, grid, radar,” Bleming proclaimed as the trash blackened.

For Bleming, West Papua is more than an injustice. It is a screen for projecting long-held fantasies of winning a good fight on behalf of an oppressed underdog. Outraged by what he sees as the plundering violence of Indonesian rule, Bleming spoke in Patton-esque bursts of bravado. “We’re going to win in Papua. Win faster than anyone thinks,” he insisted.

Anari more than tolerated his friend’s theatrical self-assurance; he gently encouraged it. And why not? In Lusk, nothing could stop Anari from role-playing a general on the cusp of certain victory. It was a tempting indulgence, given murky and tragic truths in West Papua. Indonesia’s military is more powerful by magnitudes than the likes of Anari’s planned army could ever become. The country’s strongest allies include the United States, which sees Indonesia as a key economic and military partner in Asia. And far from the commander he aspires to be, Anari is just one self-styled player among many in the disarray of activists and organizations pushing for West Papua’s freedom.

“Anari represents a long tradition of the fragmentation and organizational weakness of the independence movement,” said Richard Chauvel, a historian of West Papuan nationalism at the University of Melbourne’s Asia Institute. “These activists that pop up hither and thither—and they’re ‘presidents,’ ‘ministers,’ or ‘generals’—know that West Papua hasn’t had the capacity to threaten Indonesian control at any time since 1963. The more modestly titled activists often have a stronger basis of support in West Papua.”

Whatever his true influence, it’s possible that Anari’s winter journey to the United States could place him in danger back home. According to Ed McWilliams, a former political counselor at the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesian intelligence regularly monitors critics of the state’s iron grip on West Papua. “[Anari’s] seeming support for armed struggle would make him especially vulnerable to legal or extra-legal retaliation,” McWilliams wrote in an email.

But in Wyoming, Anari and Bleming told a very different story, one of an impending, triumphant return. “We can’t tell you the details because they’re classified, but the general has a devastating strategy he’s going to unleash on the Indonesian forces,” Bleming said as the fire died down that January evening. “It’ll be a historic rout. Right, John?”

The question caught Anari entranced with a dome of starry sky. He straightened himself and assumed a stern look. “If the world abandons us again, then, yes, we will fight,” he said. “We will kick the Indos out.”

“That’s right,” Bleming said. “They won’t know what hit ’em.”