Sea power

Who rules the waves?

China no longer accepts that America should be Asia-Pacific’s dominant naval power

Oct 17th 2015 | From the print edition

IN THE next few days, out of sight of much of the world, the American navy will test the growing naval power of China. It will do so by conducting patrols within the putative 12-mile territorial zone around artificial islands that China is building in the disputed Spratly archipelago. Not since 2012 has America’s navy asserted its right under international rules to sail so close to features claimed by China. The return to such “freedom of navigation” patrolling comes after a visit to Washington by Xi Jinping, China’s president, that failed to allay concerns about the aggressive island-building in the South China Sea.

China will protest, but for now that is probably all it will do. The manoeuvres are a clear assertion of America’s sea power, which remains supreme—but no longer unchallenged. The very notion of “sea power” has a 19th-century ring to it, summoning up Nelson, imperial ambition and gunboat diplomacy. Yet the great exponent of sea power, the American naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, who died in 1914, is still read with attention by political leaders and their military advisers today. “Control of the sea,” he wrote in 1890, “by maritime commerce and naval supremacy, means predominant influence in the world; because, however great the wealth product of the land, nothing facilitates the necessary exchanges as does the sea.”

Sea power of both the hard, naval kind and the softer kind that involves trade and exploitation of the ocean’s resources is as vital as ever. Bits and bytes move digitally, and people by air. Physical goods, though, still overwhelmingly go by sea: a whopping 90% of global trade by weight and volume. But the sea’s freedom and connectivity are not inevitable. They rely on a rules-based international system to which almost all states subscribe for their own benefit, but which in recent decades only America, in partnership with close allies, has had the means and will to police.

Since the second world war, America’s hegemonic power to maintain access to the global maritime commons has been challenged only once, and briefly. In the 1970s the Soviet Union developed an impressive-looking blue-water navy—but at a cost so huge that some historians regard it as among the factors that brought the Soviet system to collapse less than two decades later. When the cold war ended, most of that expensively acquired fleet was left to rust, abandoned in its Arctic bases.

That may now be changing. On October 7th Russia ostentatiously fired 26 cruise missiles from warships in the Caspian Sea at targets in Syria (it denied American claims that some fell in Iran). Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, milked the propaganda value: “It is one thing for the experts to be aware that Russia supposedly has these weapons, and another thing for them to see for the first time that they really do exist.” Western military planners must now contend with Russia’s demonstrated ability to hit much of Europe with low-flying cruise missiles from its own waters.

But by far the more serious naval challenger is China. From modest beginnings it has created a navy that has grown from a purely coastal outfit to a potent force in its “near-seas”, ie, within the first island chain from Japan to the Philippines (see map). It is now evolving again, into something even more ambitious. Over the past decade, long-distance operations by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) have become more frequent and technically demanding. As well as maintaining a permanent counter-piracy flotilla in the Indian Ocean, China conducts naval exercises far out in the western Pacific. Last month a group of five Chinese naval vessels passed close to the Aleutian Islands after a Russian-Chinese military exercise.

The sea’s the thing

In May China issued a military white paper that formalised the addition of what it calls “open-seas protection” to the PLAN’s “offshore-waters defence” role. A strategy that used to put local sea control first now emphasises China’s expanding economic and diplomatic influence. The primacy China once gave its land forces has ended.

The traditional mentality that land outweighs the sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests. It is necessary for China to develop a modern maritime force structure commensurate with its national security.

Taiwan remains at the centre of these military concerns. China seeks to develop not only the means to recover the renegade province (as it sees it), by military means if necessary, but also to fend off Taiwan’s main protector, America. China has not forgotten its humiliation in 1996 when America sent two carrier battle groups, one through the Taiwan Strait, to deter Chinese missile tests aimed at intimidating the Taiwanese government. America’s then-defence secretary, William Perry, crowed that, although China was a great military power, “the strongest military power in the western Pacific is the United States.”

China is determined to change the balance. It has invested heavily in everything from shore-based anti-ship missiles to submarines, modern maritime patrol and fighter aircraft, to try to keep America beyond the first and, ultimately, second island chains. China is also seeking the ability to patrol the choke points that give access to the Indian Ocean, through which most of its oil imports enter. About 40% comes through the Strait of Hormuz and over 80% through the Malacca Strait. Among the goals it appears to have set itself are to protect economically vital sea lanes; to constitute a dominating presence in the South and East China Seas; and to be able to intervene wherever its expanding presence abroad, whether in terms of investment or of people, may be threatened.

In August the Pentagon announced a new Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy. It stresses three objectives: to “safeguard the freedom of the seas; deter conflict and coercion; and promote adherence to international law and standards”. It confirmed that America was on schedule to “rebalance” its resources by deploying at least 60% of its naval and air forces to the Asia-Pacific by 2020, a target announced in 2012. Ray Mabus, the navy secretary, has asked Congress for an 8% increase in his budget, to $161 billion for the next fiscal year; he wants the navy to grow from 273 ships to at least 300. Some Republicans say that 350 is the right number.

Is America right to be worried? The way China is going about becoming a global maritime power differs somewhat from the Soviet Union’s great period of naval expansion. Apart from the powerful Soviet submarine fleet, the main purpose of which was strategic nuclear strike and stopping American reinforcements crossing the Atlantic to come to Europe’s aid, the Soviet navy was mostly concerned with expressing great-power status and extending Soviet influence around the world through “presence” missions that impressed allies and deterred enemies.

Power plays

These matter to China, too: a central element of what Mr Xi calls the “China dream” is its transformation into a military power that can cut a dash on the world stage. When large naval vessels exercise or enter port far from home they can be used to influence and coerce. It is understandable that a country of China’s size, history and economic clout should want some of that. Nor is it strange that China should want to prevent a possible adversary (ie, America) from operating with impunity near its own shores.

What makes China’s rise as a sea power troubling for the countries that rely on America to maintain the rules-based international order and the freedom of the seas are its behaviour and where it lies. The Indian Ocean, South China Sea and East China Sea are vital transit routes for the world economy. Eight out of ten of the world’s busiest container ports are in the region. Two-thirds of the world’s oil shipments travel across the Indian Ocean on their way to the Pacific, with 15m barrels passing through the Malacca Strait daily. Almost 30% of maritime trade goes across the South China Sea, $1.2 trillion of which is bound for America. That sea accounts for over 10% of world fisheries production and is thought to have oil and natural-gas deposits beneath its floor.

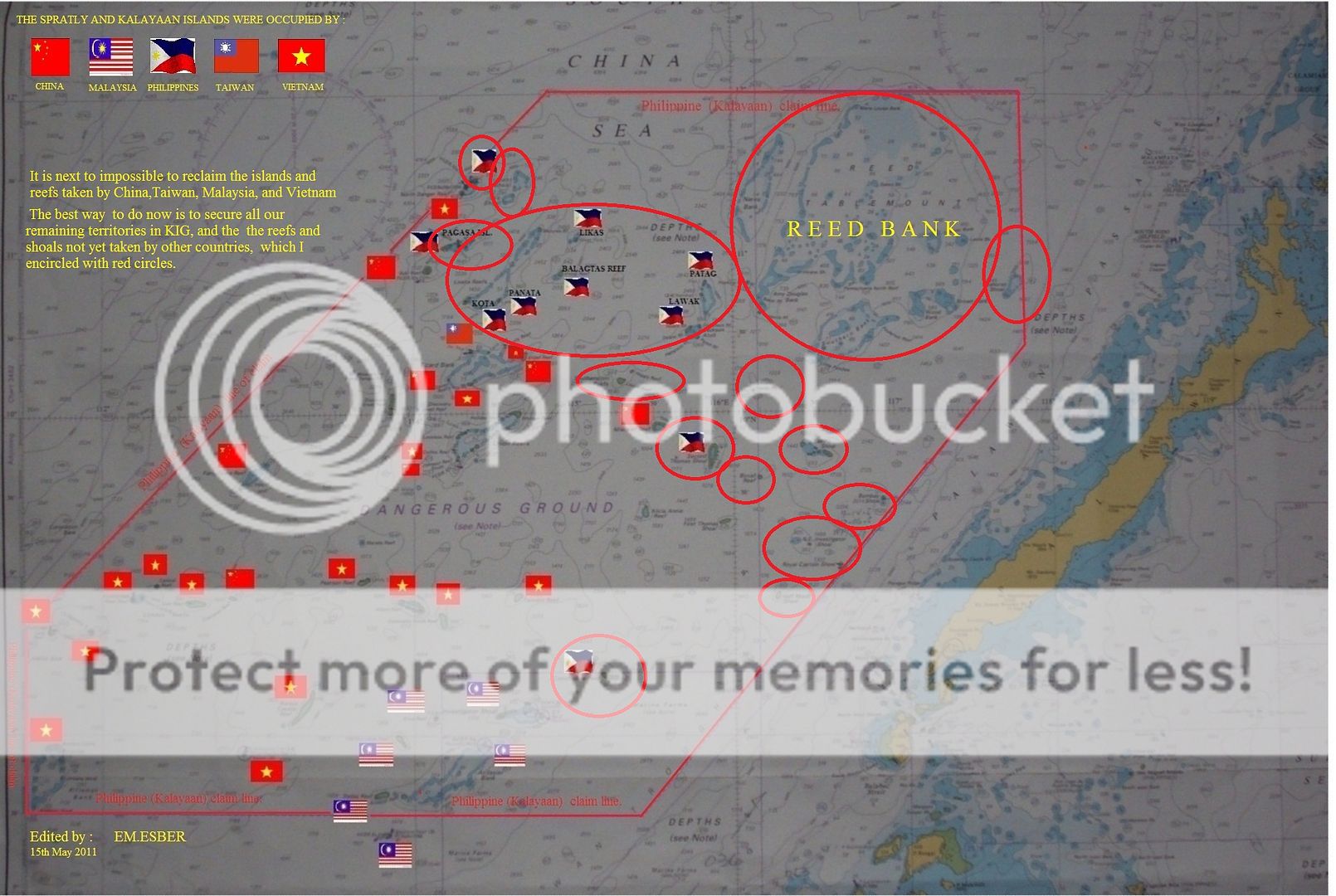

Much of this is contested, with China the biggest and most aggressive of the claimants. In the South China Sea Beijing’s territorial disputes include the Paracel Islands (with Taiwan and Vietnam); the Spratlys (with Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei) and Scarborough Shoal (with the Philippines and Taiwan). China vaguely claims sovereignty within its so-called nine-dash line over more than 90% of the South China Sea (see map). The claim was inherited from the Kuomintang government that fled to Taiwan in 1949; whether this applies only to the islands and reefs, or to all the waters within it, has never been properly explained. In the East China Sea a dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands (which Japan controls) rumbles on, though the mutual circling of coastguard vessels has become more ritualised of late.

America takes no position on these disputes, insisting only that they should be resolved through international arbitration rather than force, and that all sovereignty claims should be based on natural land features. Yet China is using its growing sea power coercively, carrying out invasive patrols, encroaching on other claimants’ waters and, most recently, creating five artificial islands in vast land-reclamation projects on previously submerged features (which, under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, do not grant entitlement to the 12-mile territorial waters). These are being equipped as advanced listening posts and three are getting runways and hangars, meaning they can rapidly be put to military use.

China is not the first to build in the area. But in less than two years it has reclaimed nearly 20 times as much artificial land as rival claimants together have in the past 40. Its bases would be easy for America to neutralise; but, short of war, they allow China to project military power much farther than hitherto. No wonder America’s national security adviser, Susan Rice, recently vowed that American forces will “sail, fly and operate anywhere that international law permits”, and that those “freedom of navigation” patrols would resume.

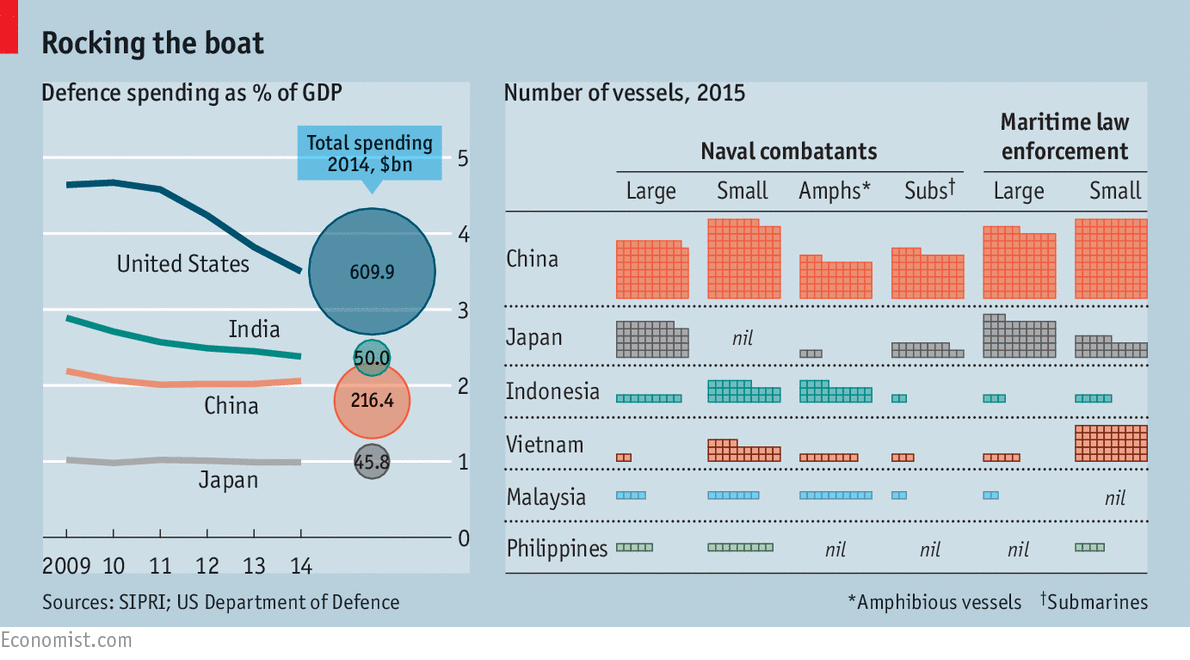

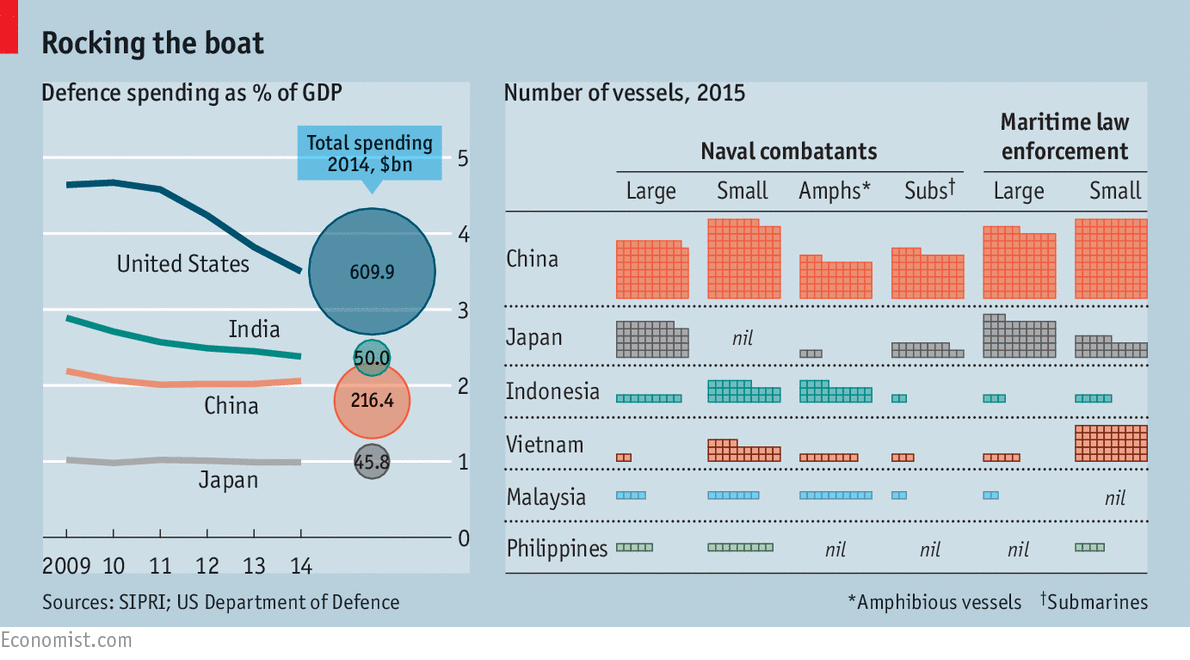

The Pentagon document notes that the PLAN now has the largest number of vessels in Asia, with more than 300 warships, submarines, amphibious ships and patrol craft. Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam can muster only about 200 between them, many of those older and less powerful than China’s (see table). This preponderance is hardly less daunting when it comes to maritime law-enforcement vessels: it has 205 compared with 147 operated by those five countries, which it often uses to stake its territorial claims while more lethal naval forces lurk over the horizon. Although nearly all the countries in dispute with China are trying to buy or build new ships, the capability gap continues to widen.

On the horizon

China could therefore threaten, if so minded, the rules and norms governing maritime boundaries and resources, freedom of navigation and the peaceful resolution of disputes. Would America be ready to face that challenge? Those who fear that America’s ultimate retreat is inevitable are almost certainly wrong. Although growing fast, China’s entire (official) defence budget is not much more than that of America’s navy alone. America has ten nuclear-powered supercarriers, one of which is permanently based in Japan. China has just one, a small, refurbished Soviet-era affair, and two more under construction. All three of America’s latest Zumwalt-class stealth destroyers (pictured), the world’s most advanced surface warships, will be deployed in the Asia-Pacific region along with other new ships and aircraft. Chinese military experts believe that the PLAN will take another 30 years to match the efficiency of the American navy.

America also has the advantage of having other navies to work with and alongside, both in the region and globally. Japan’s Maritime Self-Defence Force lacks power-projection, but is regarded as the fifth-best navy in the world and is used to exercising with the American navy. The relaxation of national-security laws last month, allowing the Japanese navy to co-operate much more closely with allies on a greater range of missions, went down badly in Beijing. And Japan is working hard with regional neighbours who are in territorial disputes with China. It has made soft loans to the Philippines and Vietnam for new patrol vessels and older destroyers.

The Indian navy is another powerful ally. As concern about China has grown, it has started to drill with Western navies, who rate its competence highly. The annual Malabar exercise with the American navy now also includes ships from Australia, Singapore and, this year for the first time, Japan. The newish government of Narendra Modi is aiming for a 200-ship navy by 2027, with three carrier task groups and nuclear-powered submarines.

Catching up with the PLAN is impossible, but the Indian navy is determined to stop the Indian Ocean becoming a “Chinese lake”. Indian strategists have long believed that China is establishing a network of civilian port facilities and underwriting littoral infrastructure projects to boost its vessels’ ability to operate in waters which the Indian government thinks should be under its dominion. China now often sends its nuclear-powered submarines into the Indian Ocean.

China has benefited as much as any other country from the hegemonic power of the American navy to preserve peace in the Asia-Pacific region. This has helped its remarkable growth. Yet it seems determined to challenge that order. It is understandable that China should want to make it riskier for the American navy to operate close to its own littoral. And for a country that wants a “new type of great power relationship”, relying on America to police the seas is demeaning, though the notion that America and its allies are threatening to blockade the sea lanes of communication that are the arteries of China’s, and the world’s, trade is fanciful in any scenario short of war. But should it ever come to war over, say, a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, China will want to deny America the ability to come to Taiwan’s aid, or at least delay it. The flip-side is that by developing a navy which intimidates its neighbours, China is driving them ever more closely into America’s embrace.

Moreover, being a strong but still second-best sea power can result in disastrous miscalculation. Germany challenged British naval supremacy early in the 20th century by provoking ruinously expensive competition in battleship construction. But it was still powerless to break Britain’s blockade during the first world war. As for Japan, six months after its surprise attack on Pearl Harbour during the second world war, it lost the decisive battle of Midway and with it a large part of the fleet it had built with such hubris.

There is nothing wrong with China regarding a powerful blue-water navy as essential to its prestige and self-image, particularly if it eventually concludes that it should be used to reinforce international rules rather than undermine them. The worry is that China itself may not know what it will do, and that the temptation to use it for more than flag-waving, diplomatic signalling and discreet bullying will become hard to resist. As Mahan observed: “The history of sea power is largely, though by no means solely, a narrative of contests between nations, of mutual rivalries, of violence frequently culminating in war.” It does not have to be like that, but America must prepare for the worst.

From the print edition: International