- Reaction score

- 146

- Points

- 710

UK War Office and PoWs of Japanese not best pleased with "Bridge on the River Kwai":

Mark

Ottawa

Letters reveal British objections to plot of Bridge on the River Kwai

War Office feared war movie would ‘not go down well with British public’

The adventure war film The Bridge on the River Kwai may have swept the board of awards and attracted acclaim as one best films of the 20th century, but the War Office was very nervous “it would not go down well with the British public”, documents reveal.

Letters between the Hollywood producer Sam Spiegel and the UK War Office, from whom he was seeking permission for RAF cooperation in making the 1957 film, show tensions over how its plot depicted the conduct of British officers.

The film is set in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in Burma. Its leading character, British commanding officer Lt Col Nicholson, played by Alec Guinness, at first refuses to allow his officers to perform manual labour on the infamous “railway of death” and the bridge linking Bangkok and Rangoon. Nicholson eventually compromises, deciding that if they are forced to work on it, they will design and build the bridge properly and with pride.

Details of behind-the-scenes clashes are revealed in letters held at the National Archives, showing War Office objections, and the anger of a member of the Fepow committee – Far East Prisoners of War – who stressed officers were obliged to focus on escape and sabotage, rather then cooperation with their Japanese captors.

On being sent the script, a Maj A G Close, from the War Office’s PR department, wrote: “I do not think much of this story. In the first instance it is quite untrue and only very occasionally resembles the facts as they were at the time. I am perhaps biased as I worked for three and a half years on this particular railway.” He had sent the script to others “and they agree with me that it would not go down well with the British public” [emphasis added].

The deputy director of PR at the War Office agreed, saying it was difficult to believe that any British commanding officers would have acted in the way that the character Nicholson did.

The scriptwriter Carl Foreman, who was blacklisted in Hollywood after admitting to being a Communist party member, and was not credited in the final film, tried to reassure the War Office, highlighting script changes, and the fact the film did portray acts of sabotage.

Eventually the War Office grudgingly agreed to RAF cooperation, but stressed it was “not entirely happy about this film story, which does contain certain inaccuracies and which does not, in our opinion, always authentically portray the behaviour and conduct of British officers”.

The War Office sought a long disclaimer at the beginning and end of the film, rejected by Spiegel, who favoured a shorter one. In the end Spiegel’s wording was used, but only at London screenings and not in other parts of the country.

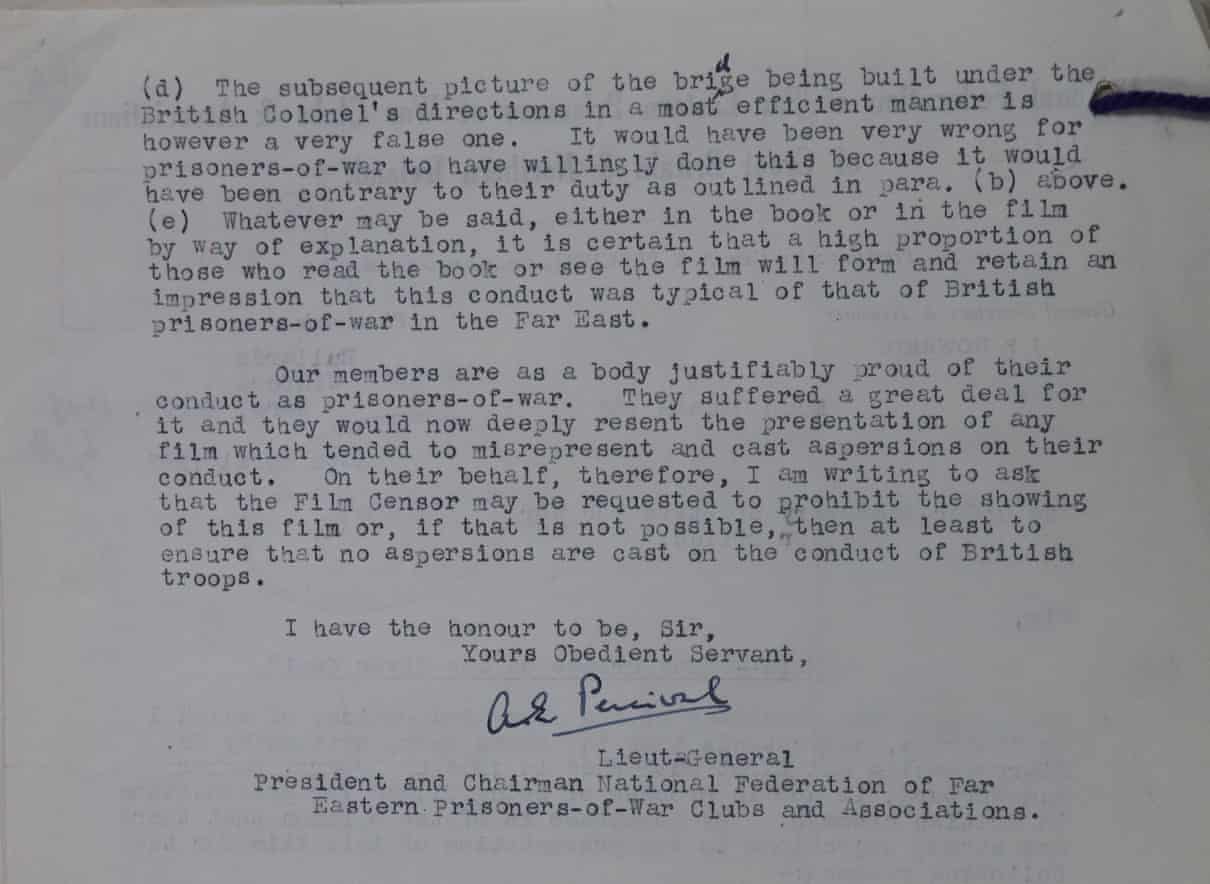

This incensed former PoWs, including Lt Gen Arthur Ernest Percival, general officer commanding Malaya, who surrendered on 15 February 1942 at the fall of Singapore, a fall Winston Churchill described as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”.

As chairman of Fepow, he wrote to the War Office: “It is reasonable to expect that the public who see the film will think that the events which take place in the film are typical of what actually happened … our members are as a body justifiably proud of their conduct as prisoners-of-war. They suffered a great deal for it and they would now deeply resent the presentation of any film which tended to misrepresent and cast aspersions on their conduct.”

In a blog to be published on the National Archives website this week, Sarah Castagnetti, its visual collections team manager, said: “These letters reveal the difficulty when fiction conflicts with a very personal reality.”

Part of Lt Gen Percival’s letter. Photograph: Crown Copyright courtesy of The National Archives

Mark

Ottawa