Argentina Shows Greece There May Be Life After Default

Joseph E. Stiglitz

Professor at Columbia University and a Nobel Laureate in Economics

Martin Guzman

Postdoctoral Research Fellow Columbia University

Updated: 07/01/2015

When, five years ago, Greece's crisis began, Europe extended a helping hand. But it was far different from the kind of help that one would have wanted, far different from what one might have expected if there was even a bit of humanity, of European solidarity.

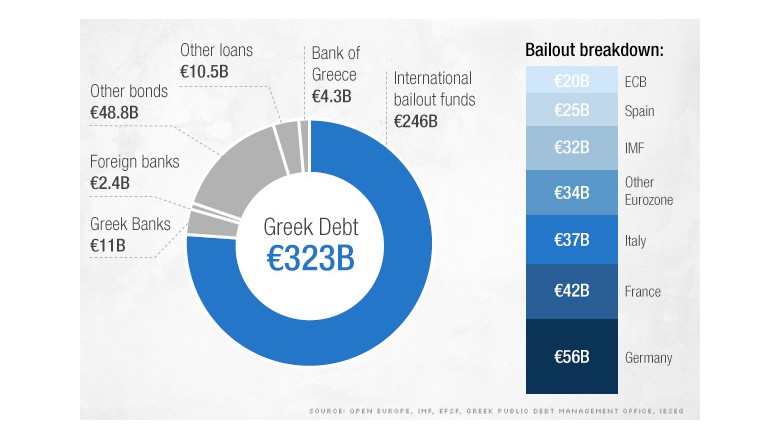

The initial proposals had Germany and other "rescuers" actually making a profit out of Greece's distress, charging a far, far higher interest rate than their cost of capital. Worse, they imposed conditions on Greece -- changes in its macro- and micro-policies -- that would have to be made in return for the money.

Such conditionality was a standard part of the lending practices of the IMF and the World Bank. Typically, when they imposed these conditions, they had little knowledge of the real workings of the economy; and frequently, there was more than a little politics in the demands. There was sometimes an element of neo-colonialism: the old White Europeans once again telling their former colonies what to do. More often than not, the policies didn't work as they were supposed to. There were huge discrepancies between what the Western experts expected and what actually happened.

Somehow, one expected something better of Greece's Eurozone "partner." But the demands were every bit as intrusive, and the policies and models were every bit as flawed. The disparity between what the Troika thought would happen and what has emerged has been striking -- and not because Greece didn't do what it was supposed to, but because it did, and the models were very, very flawed.

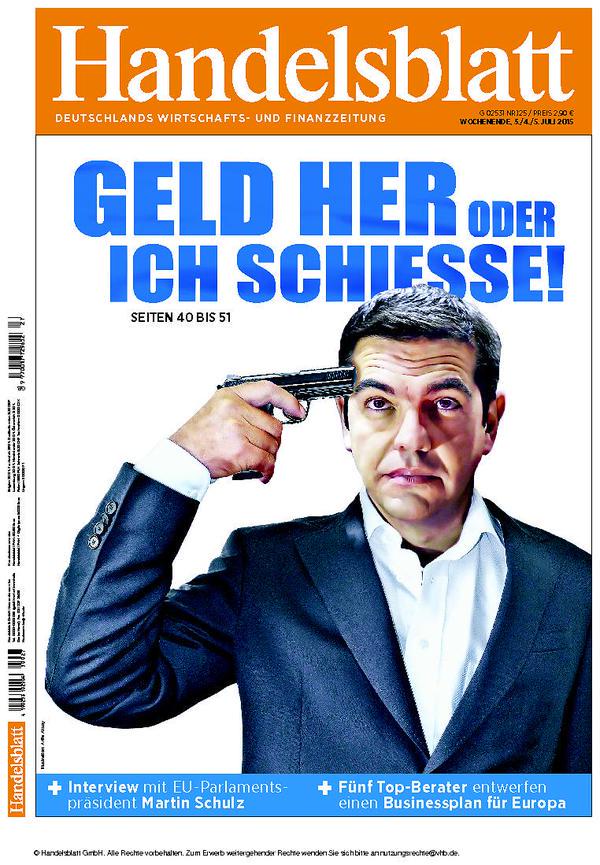

At last, after years of blackmailing Greece and demanding ever more austerity that led to a catastrophic economic depression, the Troika has finally pushed the country into the brink of default.

The situation has some important similarities with Argentina's 2001 default -- and some differences as well. In both countries, recessions turned into depressions as a consequence of austerity policies -- making the debt even more unsustainable. In both cases, the policies were demanded as a condition for assistance. Both countries had rigid currency arrangements that gave them no possibility for running expansionary monetary policies during the recession. In both countries, the IMF got it wrong, providing alarmingly flawed forecasts of the consequences of the imposed policies. Unemployment and poverty soared, and GDP plummeted. Indeed, there is even a striking similarity in the magnitude of the fall in GDP and the increase in the unemployment rate.

In Argentina, youth unemployment in particular skyrocketed and stayed high for several years. The lack of opportunities destroyed motivations and was an immense waste of the talent of millions of young people. With youth unemployment at about 50 percent in Greece, a similar saga is going on.

Defaults are difficult. But even more so is austerity. The good news for Greece is that, as Argentina showed, there may be life after debt and default.

The saga that led to the Greek default reminds us time and again of important lessons for the management of sovereign debt crises that we should have learned from earlier such events. The first one is that there is no improvement in the capacity of debt repayment without economic recovery. At the same time, there is no economic recovery without a restoration of debt sustainability.

Both in Argentina and Greece, restoring debt sustainability required a deep sovereign debt restructuring. In both cases, finalizing a "good" debt restructuring, a timely and sufficiently deep restructuring conducive to economic recovery with access to international credit markets, has proven to be quixotic. This is not due to any fault on the part of the countries, but to deficiencies in the frameworks in which negotiations were carried on.

In both cases, creditor institutions pretended that sustainability could be regained through "structural adjustments." Under intense pressure, the programs that were foisted on them were accepted and implemented -- but they obviously didn't work. Exchanging "bailout" funds -- funds that were mostly used to repay the very same creditors that were providing them -- for adjustments (and promises of even bigger adjustments) spiraled into economies that got ever weaker. In the case of Argentina, after years of suffering, the people went into the streets.

In both cases, runs on the banking system ended up with a partial freezing of bank deposits, which in the case of Argentina, triggered a full-fledged banking crisis and a subsequent conversion of deposits denominated in a foreign currency into domestic currency that led to a restructuring of domestic liabilities -- at a high cost for small domestic savers. In Greece, the consequences still remain to be seen.

Debt contracts are voluntary exchanges between creditors and debtors. They are done in a context of uncertainty: when the debtor promises to repay a certain amount in the future, everyone understands that the promise is contingent on the debtor's capacity for repayment. There is risk involved -- the reason that creditors demand a larger compensation (higher interest rates) than if they were lending under no risk.

Debt restructurings are a necessary part of the lender-borrower relationship. They have occurred hundreds of times, and they will continue occurring. The way in which they are resolved determines the size of the losses. Bad management of debt crises, such as demanding austerity policies during recessions -- in spite of theory and empirical evidence showing that austerity in recessions only makes recessions deeper -- inevitably leads to larger losses and more suffering.

Those who get saved by the bailouts (as the German and French banks in the case of Greece) usually give moral hazard as the reason to avoid debt restructuring. They claim that it would create perverse incentives; other debtors would be more inclined to "abuse" borrowing by not repaying. But the moral hazard argument is a fairy tale. Both Argentina and Greece had already paid a very high price for their debt problems by the time of default. No country in the world would be happy to follow the same road.

Greece's experience also teaches us what should not be done in a debt restructuring. The country "restructured" its debt in 2012, but it did it wrong. It was not only insufficiently deep for economic recovery, but it also led to a change in the composition of debt -- from private creditors to official creditors -- making further restructurings more difficult.

To some extent, Greece faces a more complex situation than Argentina did in 2001. Argentina's default was accompanied by a large currency devaluation that made the country more competitive and that, together with the debt restructuring, provided the conditions for a sustained economic recovery. In the case of Greece, default and Grexit would require the re-implementation of a domestic currency. It's not the same to devalue an existing currency than to create a new currency in the midst of a crisis. This additional layer of uncertainty has enhanced the Troika's capacity for pressuring Tsipras's government.

When debt is unsustainable, there needs to be a fresh start. This is a basic, well-recognized principle. So far, the Troika is depriving Greece from this possibility. And there can't be a fresh start with austerity.

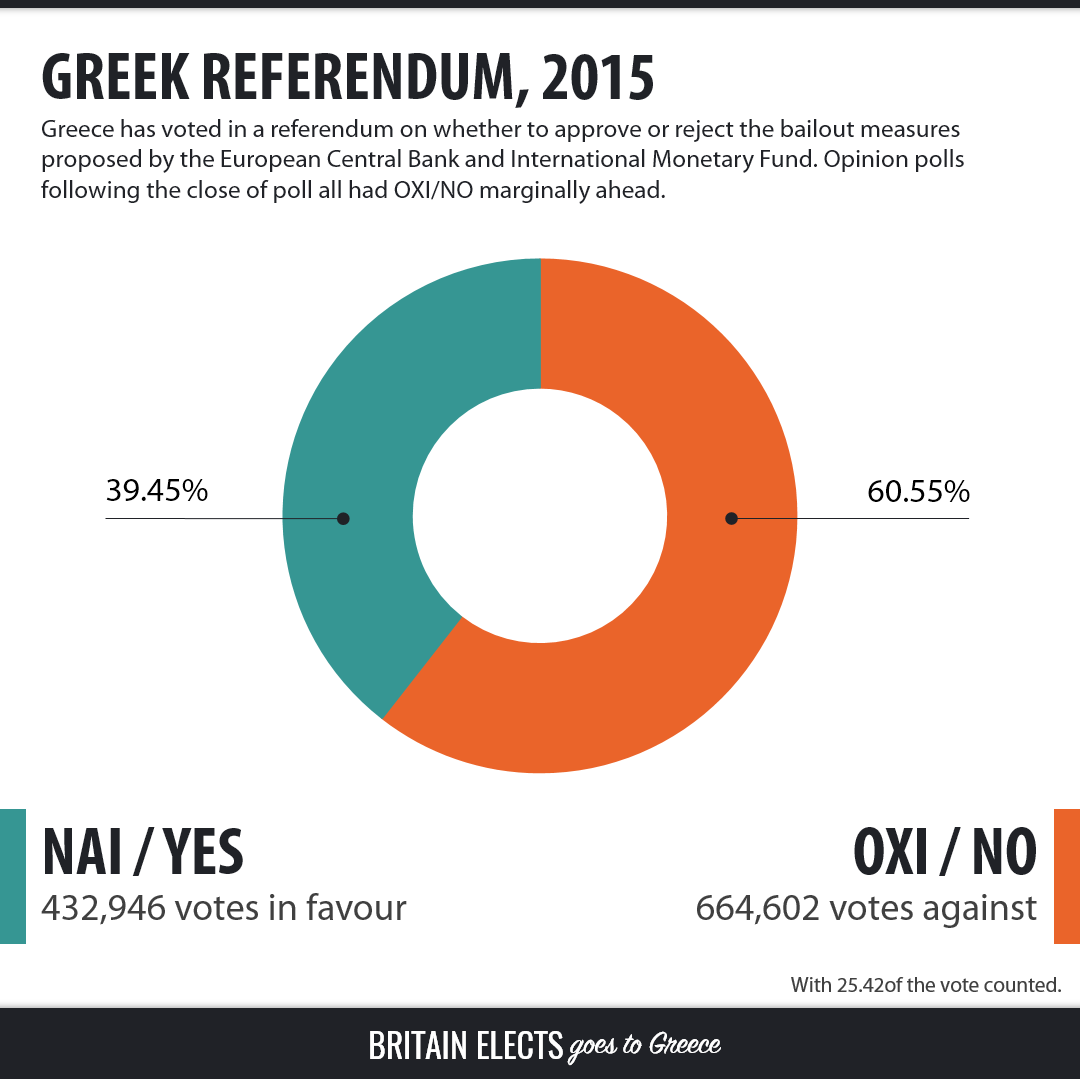

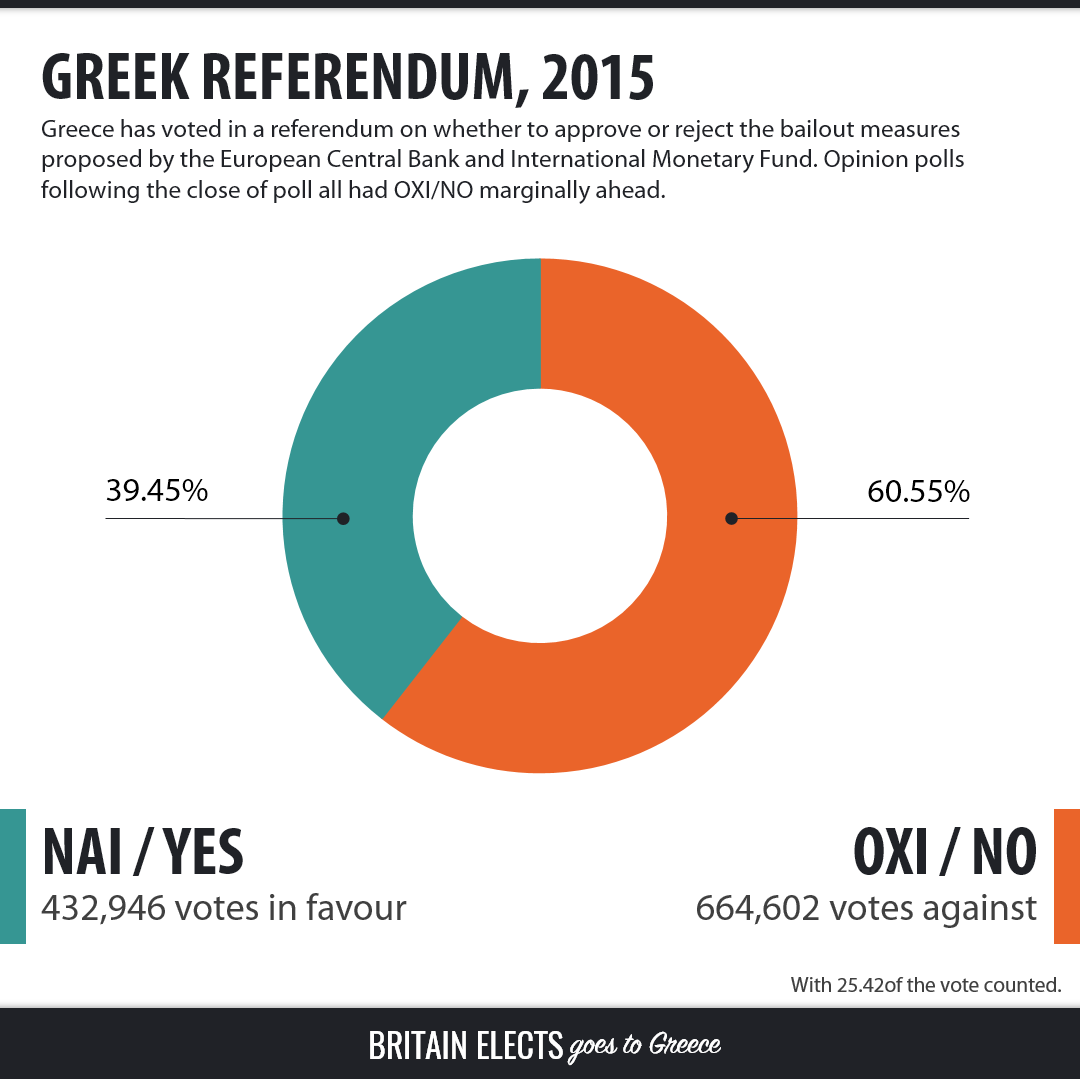

This Sunday, Greek citizens will debate two alternatives: austerity and depression without end, or the possibility of deciding their own destiny in a context of huge uncertainty. None of the options are nice. Both could lead to even worse social disruptions. But while with one of them there is some hope, with the other there is not.